The discipline of Basic Writing has a few possible dates of emergence. If one refers to it simply as remediation, then it has existed since 1870. Most, however, mark the emergence of the field as a discipline of study to the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In particular, CUNY’s open admissions policy that was enacted in Fall 1970 is credited with shifting the emphasis from remedial education to developmental education; rather than a deficit model, developmental education (of which Basic Writing is a part) focuses on student potential. In the late 1960s-early 1970s, Mina Shaughnessy of City College wrote Errors and Expectations and cofounded several publications, including The Journal of Basic Writing (Soliday 65). Shaughnessy defines the need for “a pedagogy for writing that respects, in its goals and methods, the maturity of the adult, beginning writer and at the same time admits to the need to begin where the beginning is, even if that falls outside the traditional territory of college composition” (9).

Remedial classes existed prior to open admissions. Even Harvard and Yale had classes for students whose college prep schools had not prepared them well enough (Villanueva 98). In America from 1900-1920, colleges began to differentiate student ability level by placing them into tracks. “Institutions use this strategy [differentiation of student ability levels] to resolve a fundamental paradox in American society: how to fulfill students’ aspirations– and demands– for class mobility through postsecondary education without relinquishing the academy’s traditional selective functions” (Soliday 71).

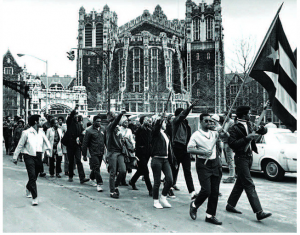

In November 1968, students demanded a change when they overtook City College’s campus and gave the administration a signed petition critiquing the city’s plan to create a system of schools that would further divide students along tracks (Soliday 71). Students pushed for the right to attend the school of their choice. The problem of preparation, or the lack thereof, persisted. Adrienne Rich taught in CCNY’s SEEK program: “Teaching at City I came to know the intellectual poverty and human waste of the public school system through the marks it has left on students– and not on black and Puerto Rican students only, as the advent of Open Admissions was to show” (19).

While the new students lacked certain skills in writing, they had other strengths. Rich defined a quality of Basic Writers that persists today, when she said their best strength was “an impatient cutting through of the phony, a capacity for tenacious struggle with language and syntax and difficult ideas, a growing capacity for political analysis which helped counter the low expectations their teachers had always had of them, and which many had had of themselves” (18).

Shaughnessy was the administrator of a Pre-Baccalaureate program before creating the Basic Writing sequence. In The Politics of Remediation, Mary Soliday explains, “Shaughnessy’s struggle to integrate her program into a traditional liberal arts curriculum challenged the anomalous status of remedial education that has been its lot for a century” (68). The creation of Basic Writing was not only about preparing students for the rigors of college-level work but also about allowing them to join the college in academic work in spite of their current level of preparedness.

In 1993, Bartholomae wrote, “I felt then, as I feel now, that the skills course, the course that postponed ‘real’ reading and writing, was a way of enforcing the very cultural division that stood as the defining markers of the problem education and its teachers, like me, had to address” (Bartholomae 6-7). Basic Writing teachers struggled with what precisely to teach. They debated how much emphasis to place on skill versus allowing the space for students to engage in college-level work on their own terms. This is further complicated when one considers that most teachers of Basic Writing have received little to no formal training in the teaching of Basic Writing.

Too often, Basic Writing scholars reinvent pedagogy rather than refer back to scholarly work already done. In an article about construction of student identity in the Journal of Basic Writing, Laura Gray-Rosendale emphasizes how scholars use the unique situations of their own schools to dictate what should be assumed about student identity. In 1993, Mike Rose pointed out that although there are 40 years of articles in JBW, zero were cited in higher education journals: “Most of us are trained and live our professional lives in disciplinary silos” (29). Most Basic Writing instructors align with some form of Rhet/Comp theory but are often at least one step away from full alignment, contributing to the nature of the disciplinary silo.

Basic Writing programs were tolerated as a necessity. Soliday explains that Basic Writing courses always reflect the current political situation of the larger economy as well as the specific schools or even the departments in which they are housed; the programs have always been used “to boost enrollments while espousing standards; to move students into professional schools without surrendering more credits to an English department; to establish a course of elective literary study while maintaining a compulsory writing program; or to fulfill certain commitments to access for historically underrepresented groups” (62).

Video about the future of Basic Writing, an interview with Rebecca Mlynarcyzk and Ira Shor at CUNY

Works Cited

Bartholomae, David. “The Tidy House: Basic Writing in the American Curriculum.” Journal of Basic Writing 12.1 (1993): 4-21. Print

Rich, Adrienne. “Teaching Language in Open Admissions.” Teaching Developmental Writing: Background Readings. 1973. 4th ed. Ed. Susan Naomi Bernstein. Bedford: Boston, 2013. 12-26. Print.

Shaughnessy, Mina. “Some Needed Research on Writing.” Teaching Developmental Writing: Background Readings. Dec. 1977. 4th ed. Ed. Susan Naomi Bernstein. Bedford: Boston, 2013. 12-26. Print.

Soliday, Mary. The Politics of Remediation. U of Pittsburgh P: Pittsburgh, 2002. Print.

Villanueva, Victor. “Subversive Complicity and Basic Writing Across the Curriculum.” Journal of Basic Writing 32.1 (2013):97-110. Print.

Photo Credit:

“History of CCNY.” West Harlem. WordPress, 2011. Web. 17 Sept. 2015.

Video Credit:

“The Future of Basic Writing: How Can We Grow the Field?” YouTube. YouTube, 30 Aug. 2014. Web. 17 Sept. 2015.